When I was growing up, my older sister was like a third parent to me. If not for Jenni, I wouldn’t be the person I am today. My sister is several years older than I and the product of my mother’s first marriage so is actually my half sister. But seeing as both my parents had full-time jobs (and dad was often at the bar after work,) Jenni was like a full-time parent.

Allston #1, 2001

My older sister opened my mind to music, politics, and the larger world outside of my small, working-class hometown of Hudson, Massachusetts, where I’d probably still be if it wasn’t for her. Don’t get me wrong: there’s nothing wrong with where I grew up. Hudson is a quaint, former shoe-mill town, midway between Boston and Worcester, on the 495 beltway. Its greatest claim to fame is that Nuno Bettencourt, lead guitarist of the rock band Extreme (famous for their acoustic ballad and one-hit wonder “More than Words”), grew up there. I was never really into them, and neither was my sister whose musical tastes tended more towards what was then called “alternative” music. Jenni introduced me to a lot of cool bands.

But the greatest gift my sister imparted was that she got me into art. When she was in high school and I was still in elementary, Jenni would come home and teach me what she learned that day in art class. I remember her teaching me the rules of perspective in the bathroom of my boyhood home. The gridded tile-work of the walls served as useful guides in what was one of my first fairly well-rendered drawings. One year for Christmas, when I was in high school and she was studying graphic design at the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, Jenni gave me my first camera: a Pentax K-1000, which I still have.

■ ■ ■ ■

What I now call The Square Project began in 2001, a few months before 9/11, during a transatlantic postal art exchange between Jenni and me while she was studying design in London and I was in a photography course at UMass Boston. I was trying to figure out what I should shoot for a final project around the time we began playing around with – for whatever reason – the multiple meanings of the word square in our mailings, combining both its formal properties as a design element with its slang use as a hipper-than-thou affront: “You are so square!”

London, 2007

This got me thinking about how something so simple could work on so many levels. I was shooting with medium format film, which is square, so it just made sense to begin photographing square things I found in the world. I have been doing that ever since. What began as a playful mail-art correspondence evolved into a serious art project, and ultimately my graduate thesis, “The Persistence of and Resistance to Structure: The Grid-Square Construct In Western Visual Culture,” which I dedicated to my sister.

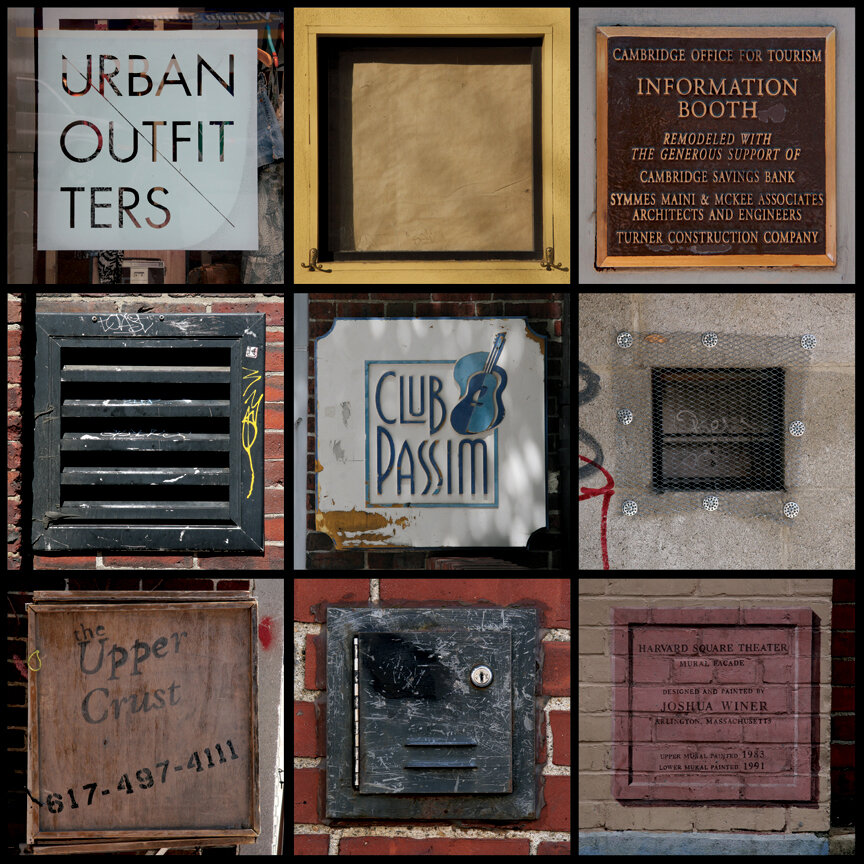

The Square Project documents various square forms I find on my many explorations of the city. The urban landscape is full of squares: buttons, hatches, logos, signs, and windows, to name but a few. There is also the market or public square, where commercial and social activity is concentrated, such as with Harvard Square, Times Square, and Trafalgar Square. I photograph squares wherever I go, in whatever city I visit, and organize them in a grid format, recalling the urban layouts from which they were found. Squares are my markers, the coordinates of my wanderings.

Harvard Square, 2009–2014

The square can be an empty frame or a node of information, like a point on a graph or a pixel on a screen. It is banal and profound, prosaic and sacred. In its static form it is the bureaucratic checkbox on a survey or the symbol for the stop button on remote controls. But the square is also a symbol of humanist universalism, as conveyed in da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. It is also the modernist black void of Malevich's Black Square. When squares work in unison with one another they create gridded networks as with the giant Pop-art portraits of Chuck Close or in digital interfaces, where each individual pixel is a single point of light in the raster image.

The word square has significant meaning in American culture and history. Grids and squares are especially evident in the American landscape. Since the Land Ordinance of 1785, which superimposed the grid over the country west of Appalachia, following the Louisiana Purchase, the young republic was divided into square lots of land. This is where the expressions “fair and square” and “a square deal” came from. The American grid is visible to the naked eye from an airplane window when flying over the Midwest: each square lot of farmland, equal in size, and as flat as an Agnes Martin painting, represents the ideals of the new nation: E pluribus unum.

While squares are ideal for organizing land into fields, townships, cities, counties, and states, it produces a mind-numbing monotony. Flying over Minnesota, British travel writer and novelist Jonathan Raban observes in “Mississippi Water,” an article for Granta Magazine:

The great flat forms of Minnesota are laid out in a ruled grid, as empty of surprises as a sheet of graph paper. Every graveled path, every ditch has been projected along the latitude and longitude lines of the township-and-range survey system. The farms are square, the fields are square, the houses are square; if you could pluck their roofs off from over people’s heads, you’d see the families sitting at square tables in the dead center of square rooms. Nature has been stripped, shaven, drilled, punished, and repressed in this right-angled, right-thinking Lutheran country. It makes you ache for the sight of a rebellious curve or the irregular, dappled color of a field where a careless farmer has allowed corn and soybeans to cohabit.

Aerial view of a square-lot homestead in the American heartland.

This same zooming-in effect used by Raban in his description of the Midwest is equally applicable to a smaller, denser area. A cityscape, like that of New York City, is ideal: Starting with an aerial view of Manhattan, with its gridiron street plan of orderly, squared blocks. Narrowing in further, were you to “pluck” the roof off the Museum of Modern Art, say, a block-like modernist building itself, you would find museum patrons, security guards, and docents standing in and walking through squarish galleries, perhaps even looking at square art by early European modernists like Malevich and Mondrian or postwar American minimalists like Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, and Frank Stella. Midwestern farmland and modern art have more in common than you might think.

Please remember to check this space for later segments of "Back to Square One,” appearing in January and February 2021.